April 2019 – Sir Kai Ho

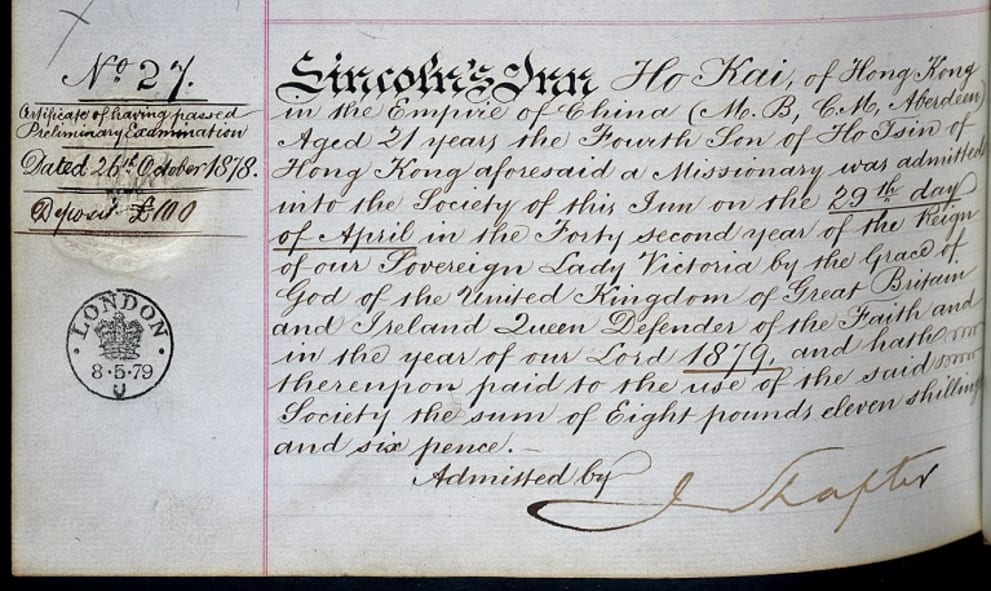

One hundred and forty years ago this month a Hong Kong Chinese man was admitted to the Inn who was to have tremendous influence there at the turn of the twentieth century but has been, perhaps, overshadowed by his brother-in-law Wu Ting Fang. He was born Ho Shan-Kai on 21 March 1859 but dropped “Shan” as it was common to all his brothers. He was the fourth son of Rev Ho Tsun-shin (alias Ho Fuk-tong) of the London Missionary Society who was the first ethnic Chinese Christian pastor in the colony. His father was not only an Anglican minister but a very successful business man, whose property investment allowed all his sons to be educated abroad. Thus, after attending the Government Central School, Ho was sent to Palmer House School in Margate in 1872. He then went to Aberdeen University to study medicine and graduated in 1879.

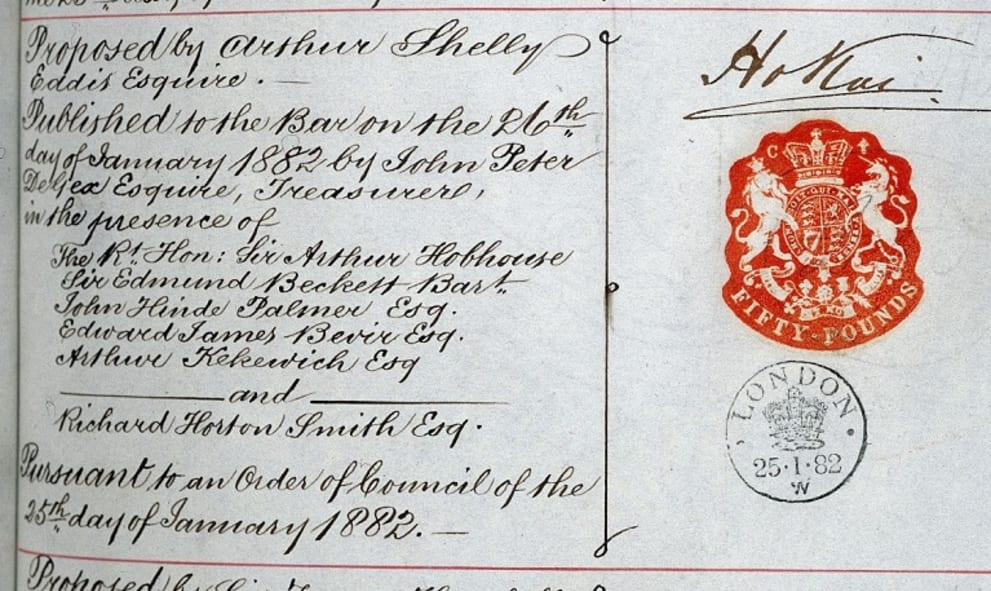

It is unknown why he decided to study law as well as medicine but he was admitted to the Inn on 29 April 1879 and passed his bar exams in Michaelmas term 1881. He was called to the bar on 26 January 1882 along with eleven other gentlemen. These included Robert Stewart Menzies who was a Scottish Liberal MP; George William Tallents, twice Mayor of Westminster; William Robert Sheldon, a government lawyer who became a bencher and; John Wanklyn McConnel, who made his career in the family cotton spinning business rather than law and was a surviving passenger from the sinking of RMS Luisitania.

It was here in London that Ho met his first wife, Alice Walkden, the eldest daughter of the late John Walkden of Blackheath. They probably met through their church connections and were married at St Aubyn’s Congregational Church, Upper Norwood, on 13 December 1881. A year later they returned to Hong Kong taking some of her siblings with them. They made their home in a house named “Craigengower” on Bonham Road which later gave its name to the Craigengower Cricket Club. Tragically Alice died of typhoid fever in June 1884, shortly after the birth of their daughter. Ho settled on her everything left by her mother and the infant girl was taken back to England by Alice’s relatives to be brought up by her family. Her death must have been a great loss to him as he financed, using all his savings, the building of a hospital in her memory which opened in 1887. However Ho later re-married Lily Lai Yuk-hing in 1885, an American-Chinese eleven years his junior, with whom he had ten sons and seven daughters.

In Hong Kong he opened a medical practice but the local Chinese population, still entrenched in the ways of traditional Chinese medicine, were uninterested in western medical treatment unless it was offered free of charge. He quickly switched his career from medicine to law. He did not abandon medicine completely as he became a lecturer in medical jurisprudence and physiology at the newly formed Hong Kong College of Medicine of Chinese. It had been established by the London Missionary Society and was the first teaching institution in Hong Kong to adopt and accept western medical practice. One of its first students was Sun Yat-sen who was to become the founding father of the Republic of China. They were to become friends and Ho became a political mentor to Sun and vocally supported him all his life in his quest to overthrow the imperial Qing dynasty in China. Their political thought diverged on the subject of democracy. As the historian Kit-ching Chan Lau points out “Ho’s ideal of democracy might have been in some way responsible for the moulding of Sun’s political thought, republicanism was certainly not Ho’s recommendation for China. He believed in the efficacy of democracy as practised in the form of a constitutional monarchy”. The ultimate end of Ho’s reformist ideas was the realisation of democracy in China through the adoption of western democratic institutions, elections and a parliament.

In order to help reform Hong Kong, Ho became an unofficial member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council. He believed that all Chinese, whatever their station in life, from the most successful business man to the lowliest rickshaw coolie, were all part of the Hong Kong story. He therefore sought legislation that would accommodate their interests and sought to limit legislation that would discriminate against Chinese inhabitants. He was, however, often torn between what was good for the stability and prosperity of the colony, what was good for the Chinese population and what benefited his own finances. This clash of interests, for example, meant he strongly opposed the passing of the Public Health Ordinance in 1888 since, although it was an important step in the development of Hong Kong’s public hygiene, it would go against the property interests of the Chinese business elite of which he was a leading member.

Unfortunately, Ho fell between two stools – he was neither fully Chinese nor fully British. While very much Chinese at heart Ho wore western clothes and was said to be the first Hong Kong Chinese to do so. He had a British education, adopted western ways and political ideas, and had an English wife yet the snobby colonial elite would not allow him to join their exclusive clubs as he was simply considered “not one of us”. he nonetheless spent his whole life upholding British values. Despite this, towards the end of his career, even his loyalty to Britain was questioned by high ranking English officials who privately thought his first loyalty was to revolutionary China, although there was no evidence for this. Even the Chinese communists labelled him a running dog of British imperialism. His “Britishness” earned him a CMG in 1902 as a reward for services rendered to the Crown in the colony. This was followed in 1912 by a knighthood making him the first Hong Kong Chinese to receive the honour. It was in the same year that he went into partnership with his son-in-law, Au Tak, in a land reclamation development project of houses and recreation grounds. The project was named Kai Tak Bund after the two men and the fact it would be next to the sea. The venture was a failure but limped on after Ho’s death until it was liquidated in 1924. The land was taken back by the government and would later become the site of Kai Tak airport, which served the colony until 1998.

The failure of his various business projects and ill health led to his early death on 21 July 1914 at his home at 45b Robinson Road. His obituary in the South China Post on the following day described the event thus “yesterday morning heart trouble set in with tragic rapidity and before either European or Chinese doctors could reach the house, he had passed away in the midst of a sorrowing family, with whom every sympathy will be felt”. His friends met the expenses of his funeral which was attended by all the great and the good of Hong Kong and he was buried near his first wife in Happy Valley cemetery. Incredible as it may seem for a barrister with a large family he died intestate and penniless leaving only the furniture in his house and a few law books in his office. Fortunately for his widow friends and family rallied round to meet their needs and in time the whole family re-located to Shanghai in the care of an influential uncle.

His newspaper obituary sums up Sir Kai’s life aptly when it stated that he “stood foremost amongst his fellows as a gentleman of high principles and as one who had turned the education of the west into channels most likely to benefit the Chinese … and never scrupled to express his honest opinion in public on all matters pertaining to the welfare of his countrymen… He gave his time ungrudgingly in all departments of public service and it was only his health – not his inclination – that compelled him to seek a quieter sphere after 25 years of active participation in the public life of the colony”.

Here was someone who despite not fully belonging to either his birth ethnic group nor his adopted adult ethnic group managed in his lifetime to bring about understanding and agreement between the two groups for the stability and future of Hong Kong.