Celebrating Black History Month: Francis Williams – earliest known black member of Lincoln’s Inn

For Black History Month 2018, Inner Temple Library put together an excellent resource which celebrated black history at the Inns of Court. It highlighted important individuals both past and present who had made their mark on the legal world, including England’s first black barrister Christian Frederick Cole who was called to the Bar at Inner Temple in 1883.

However not all members who joined the Inns of Court went on to be called to the Bar. Prior to the legal education reforms of the nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for individuals to join the Inns of Court looking for patronage and social connections rather than to necessarily qualify as a barrister. This can lead us to wonder about the first black members of the Inns who were admitted but did not go on to qualify as barristers.

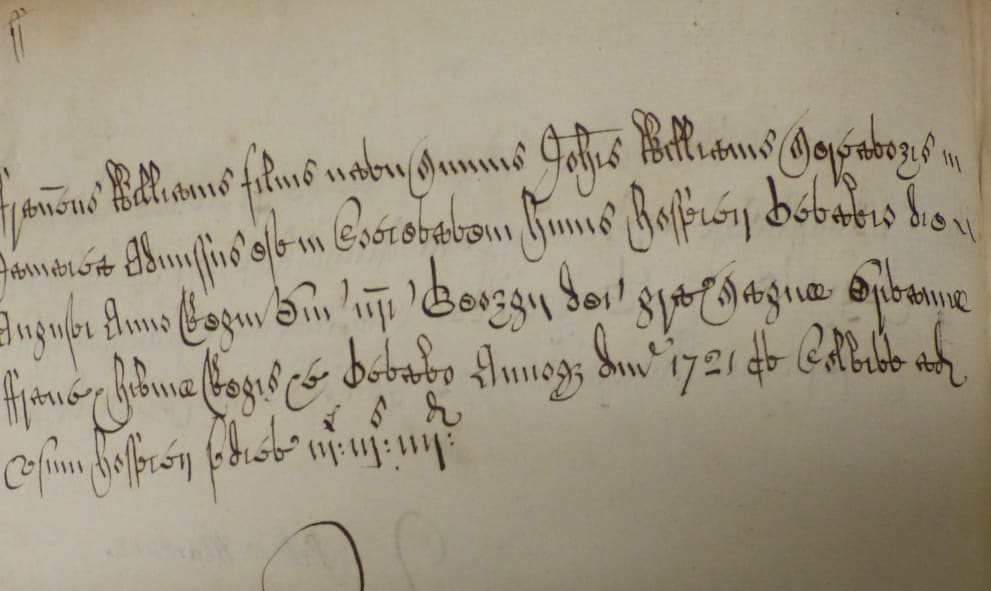

Trying to research early black history in the archives can be difficult. The Inn’s records, especially the earliest ones, are often sparse in what they record, tending to focus on minimal administrative detail. The admission registers, for example, initially just recorded the name of the individual and nothing else. In the late sixteenth century the name of a member’s father and their place of residence begins to be recorded which makes research easier. In looking at the registers more closely one entry stood out. It was an entry for Francis Williams, who is recorded as being admitted on 8 August 1721, the youngest son of John Williams of Jamaica, merchant.

It became clear that this was Francis Williams, a well-known eighteenth century Jamaican scholar and writer. He was born around 1697 to John and Dorothy Williams, a free black couple in Jamaica. A definite birth date for him is not known but what is believed to be a record of his baptism, and that of his older brother Thomas, is documented in the parish of St Catherine’s Jamaica on 26 December 1697.

Francis Williams’ father had been freed by the will of his former master, who died in 1697. Following his release from enslavement he acquired significant property and became a wealthy merchant. The status of the Williams family was extraordinary as through the private bill system of the Jamaica Assembly, John Williams strove over time to gain rights for his family that were given almost exclusively to white people, including the right to trial by jury.

Francis Williams was well known in Jamaica and in England as a writer. He appears to have been the earliest black writer known in the British Empire. The fullest account we have of him is recorded in Edward Long’s three volume History of Jamaica, published in London in 1774, twelve years after Francis Williams’ death. Long was not an impartial biographer, he was an absentee plantation owner and former judge in Jamaica. He even states in his work that ‘I have before alleged, to prove the inferiority of the Negroes to the race of white men.’

Edward Long and other defenders of slavery were quick to deny Francis Williams’ work having any poetic achievement, finding his Latin verses a clear challenge to their theories of white supremacy which upheld the plantation societies. Long’s bigoted belief in white superiority led him to disparage Francis Williams’ achievements and provide misinformation on his life.

Although there is a lack of clarity about Francis Williams’ time in England, we do know that he was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn on 8 August 1721. There is no call listed for him, but as he returned to Jamaica in 1723 his legal studies may have been cut short. Alternatively, as mentioned previously, at this time members were often admitted without necessarily having any desire to be called to the Bar.

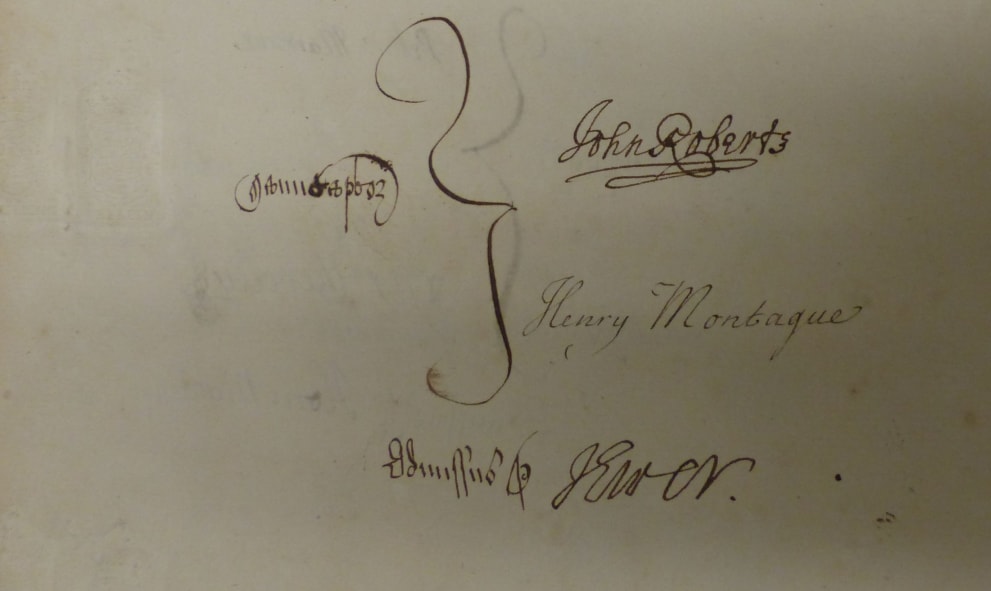

An important function of the early admission registers was financial: each admission was signed not only by the reader or bencher who authorised the admission, but also by a couple of sureties or manucaptors. These were members of the society who had proposed the new member and who were bound to ensure his payment of dues to the society. The entry records two manucaptors: John Roberts and Henry Montague. Little information could be found on these men, although it appears that they went on to become Benchers of the Inn and Treasurer (John Roberts in 1745 and Henry Montague in 1752). There is sadly no further information to give us clues as to how they knew Francis Williams but it shows that he had connections with members of the Inn and was able to find the support he would have needed for his admission.

According to one account, support was not always given to Francis Williams during his time in London. In an anonymous editorial comment in the Supplement to the Gentleman’s Magazine 1771 it is claimed that Francis Williams had the friendship of the famous surgeon William Cheselden and was admitted to meetings of the Royal Society. However, on being proposed as a member he was rejected ‘on account of his complexion.’

In July 1723, John Williams died. Francis Williams returned to Jamaica soon after and appears to have spent the rest of his life there. In his book Edward Long claims several things about his time there but one assertion, that Francis Williams, kept a school in Spanish Town, teaching reading, writing, Latin and mathematics, is partly corroborated by the rector of St Catherine’s Jamaica who wrote of knowing Francis Williams during this period when he kept a school.

Following the outbreak of the First Maroon War, a conflict between the Jamaican Maroons and the colonial British authorities, an act was passed ‘for the better regulating slaves’ and it also placed a number of restrictions on free black people. Francis Williams objected to this and took his case to the authorities in England claiming that it was an infringement of his rights bestowed on his family by previous acts. The Council of Trade and Plantations agreed and the act was eventually disallowed by the King in Council.

Francis Williams died in 1762 and was buried at St Catherine’s church, Spanish Town. His legacy lives on through Edward Long’s account which despite being heavily prejudiced provides us with the only known surviving literary work written by Francis Williams. It is a poem written in Latin and addressed to George Haldane on his taking on the governorship of Jamaica in 1759. Memorable lines which have been seen to assert the poet’s sense of his own worth as a black man and black writer, include:

‘Ipsa colorise gens virtus, prudential; honesto

Nullus inest animo, nullus in arte color’

This translates as ‘Worth itself and understanding have no colour; there is no colour in an honest mind or in art.’

Today Francis Williams’ history is made problematic by the fact that he and his family profited from the labour of enslaved Africans. However, his legacy is still extraordinary and his status as a free, educated black man was a clear challenge to the prejudiced thinking of much of society at this time.

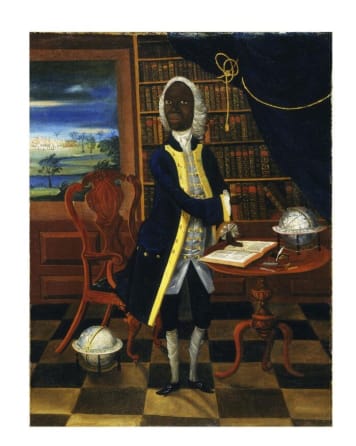

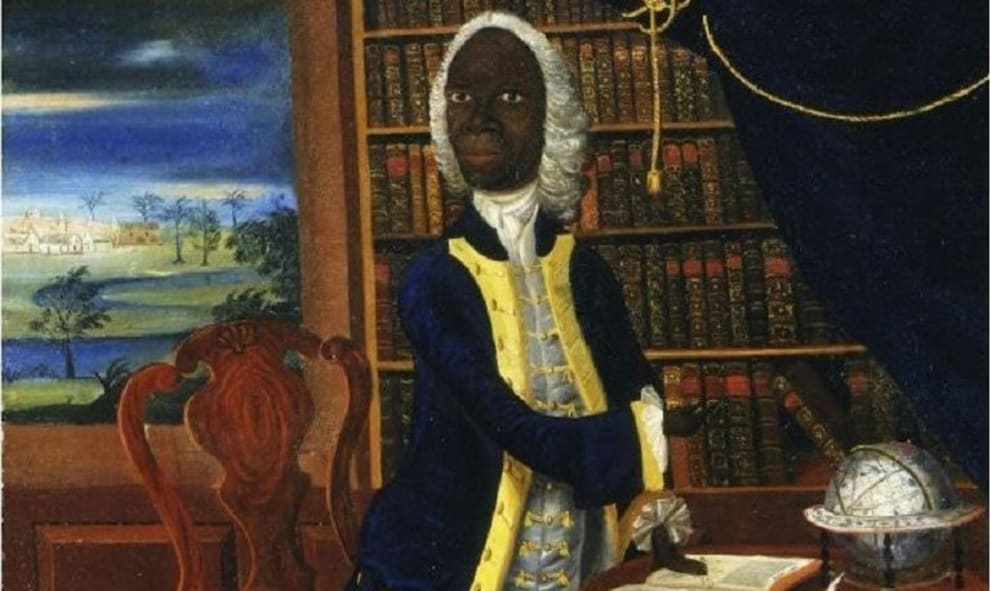

Although there is much about his time in England that remains a mystery it is remarkable to find these traces in the records. He is also memorialised in an oil painting now in the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A) in London. Dated circa 1740 the portrait is believed to show him in his library in Spanish Town, Jamaica. An open book headed Newton’s Philosophy is open before him and the V&A website describes how ‘a globe of the world by the chair, and the celestial globe, dividers and other instruments on the table, tell us that Williams studied astronomy, mathematics and geography. The quill and ink indicate his status as a writer.’ Interestingly the provenance of the portrait shows that it was owned by a direct descendant of Edward Long. This raises questions as to whether Edward Long commissioned it, and if he did why he did so, and whether it was intended as a caricature. However regardless of these unanswered questions, the portrait survives as a testament to Francis Williams achievements and his significance.

You can explore the portrait online at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/francis-williams-a-portrait-of-a-writer?gclid=EAIaIQobChMImeL9o82w8wIVq0aRBR30xQgrEAAYASAAEgLlHPD_BwE