February 2017 – The Admission of Gwyneth Bebb

In 2019, 100 years will have passed since the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act enabled women to have careers at the bar, and 2023 will see the 100 year anniversary since the first women were called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn.

In anticipation of this, on 15 March this year, the Inn is holding a Women’s Forum: Celebrating Women at the Bar: Past, Present and Future. In celebration of this upcoming event, this Archive of the Month looks at Gwyneth Bebb (married name Thomson), who was one of the first women admitted to the Inn after the Act was passed on 23 December 1919.

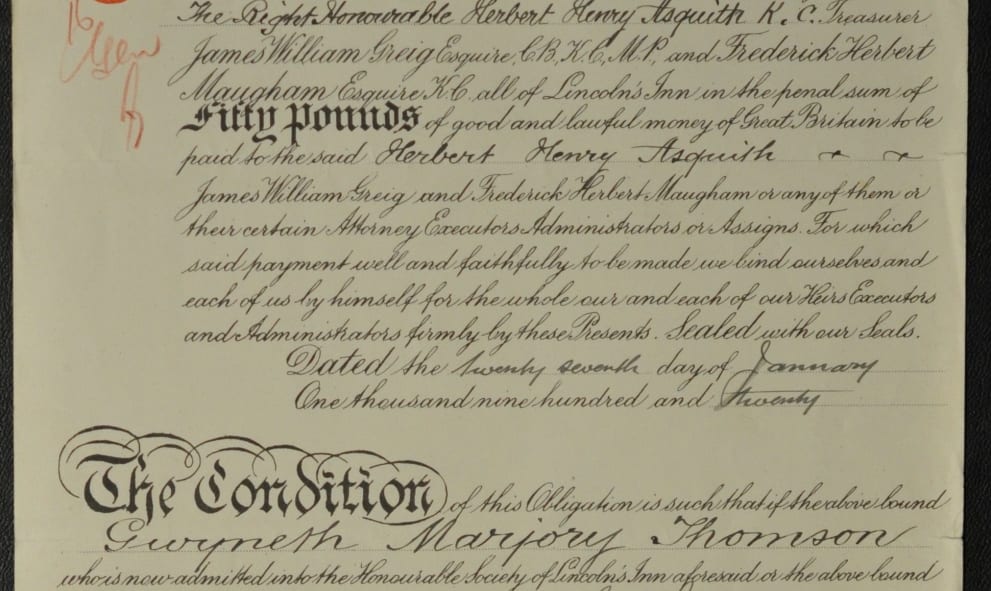

Gwyneth Bebb had long fought to establish her right to enter the legal profession. She had come to public attention in the 1913 landmark case Bebb v The Law Society, when she challenged the Law Society’s refusal to allow women to become solicitors. She lost the case, which ruled that women were not ‘persons’ under the meaning of the Solicitors Act of 1843, and continued to prohibit them from practising law. She had been supported by her solicitor John James Withers (founder of the City firm), and her counsel Stanley Buckmaster QC (later Lord Buckmaster and Lord Chancellor). These men continued to back her subsequently, and in 1920 they acted as her bondsmen by signing her admission bond for the Inn (pictured below).

Her admission to the Inn had not been a straightforward process. Her original petition for admission had been put before the bench in 1918. Her petition was referred to, in the Society’s Black Books, as a ‘communication from a Lady’ when it came before the Council on 17 December. Assent for her application was moved by Lord Buckmaster, and seconded by Sir Frederick Pollock. A decision on her petition was held over until the next Council, whereupon it was decided that her application was part of a much larger concern, which was of ‘great national importance’. Therefore the adopted stance of the Inn (in consultation with the other Inns of Court) was that no woman ought to be admitted as a member of the Inn until the larger issue, concerning the opportunities that should be opened up to women, had been dealt with by the authority of Parliament.

The diplomatic wording of the Council’s decision in 1918 shows that future change was seen to be conceivable (although not yet, perhaps, inevitable). In December 1919, with the Act set to be passed, Gwyneth Thomson renewed her application for admission. However Council ordered that this should stand over until the Act had officially passed. On 23 December the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act received the Royal Assent, and on 24 December the Inn’s Steward wrote to Gwyneth Thomson to invite her to attend to sign her bond for admission on 7 January 1920. Had she been able to do so, she would have been the first woman to be admitted into Lincoln’s Inn. However she wrote to say this would not be possible; as she had gone into a nursing home on 22 December (to give birth to her daughter Diana). As a result she could not be admitted until 27 January 1920, making her the second woman to be admitted to Lincoln’s Inn (the first being Marjorie Powell).

Although this was no doubt a welcome breakthrough for Gwyneth Thomson, the effect must have been rather undermined by the length of time that had elapsed since originally applying. This is referred to by her when, in a letter to the Inn’s Steward, she asks for confirmation of her original bondsmen. She observes that she does not have the original application and that, ‘as you will remember, it is rather more than a year since I applied.’

Gwyneth Thomson’s admission papers survive in the Archive, and include her original admission forms and accompanying letter, from her first application in 1918. In her letter she cites her extensive experience which included studying jurisprudence at Oxford, (where she achieved a first class in her examinations, but, in accordance with university regulations relating to women students, was not awarded with her degree); working as National Service Commissioner of the Midlands and then as Assistant Commissioner for Enforcement, Head of the Legal Department of the Ministry of Food in the Midlands. This role gave her ‘the responsibility of deciding as to whether proceedings shall be instituted, and of advising on the law, evidence and procedure of prosecutions undertaken in the area for offences under the Food Orders.’ She highlights the importance of her role by observing that fifteen of these appointments were made across the country and that of the other fourteen places, nearly all were held by members of the bar, with the rest being solicitors of long standing. She stresses the merits of admission to the Inn in relation to her current role, and her desire to practise as a barrister in the future.

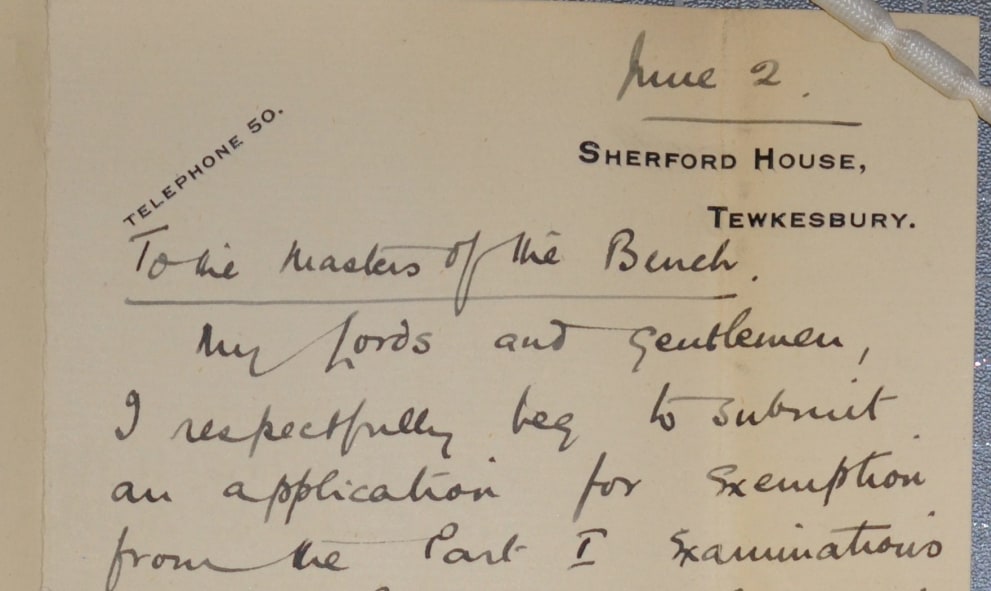

Once admitted, Gwyneth Thomson next appears in the Archive when she makes a petition to Council in June 1921. She asks for exemption from the Part I examinations in Real Property and Conveyancing, and Constitutional Law and Legal History, as she was examined in those subjects whilst at the Honours School of Jurisprudence at Oxford.

Being granted admission to the Inn was the beginning of a difficult struggle to balance competing demands, and her letter talks of how between coming down from Oxford and being admitted to Lincoln’s Inn she has ‘given hostages to fortune’ with a young family to take care of and a full time job, in addition to being a student. She assures the Council that ‘I am undertaking my position as a student very seriously’ and that she is ‘anxious now to devote all my available spare time to my final examination.’

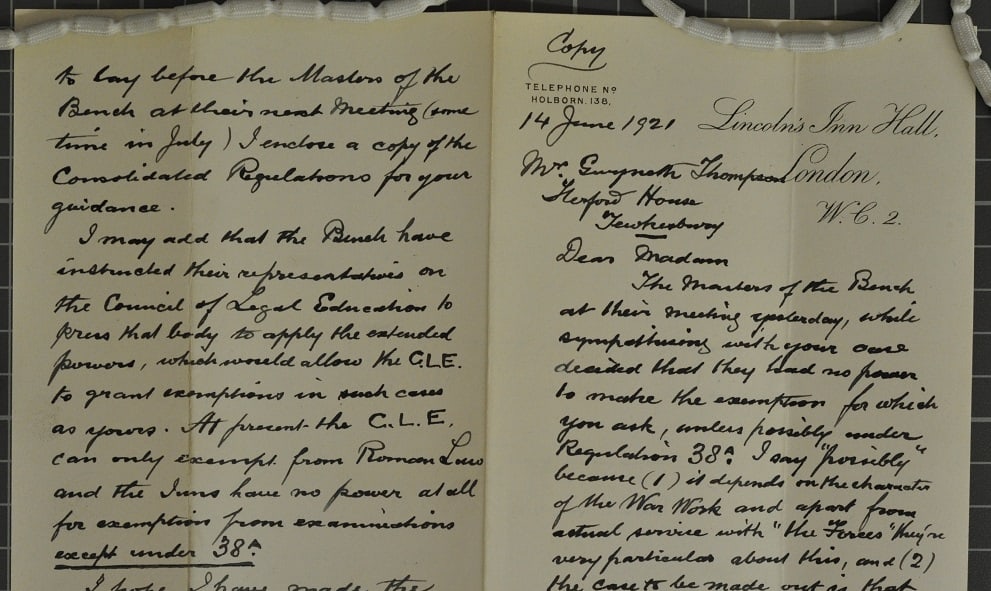

The Masters of the Bench respond saying that while they sympathise they do not have the power to make such an exemption (see reply pictured below). They stress that at present the Council of Legal Education can only exempt from Roman Law, and the Inns have no power of exemption at all from examinations except under regulation 38A. This exemption related to War work, and it is suggested that if she can put forward a reasonable case as to the nature of the War work she has been involved in, and how such service prevented her from passing such an examination, it would be considered. However it is clarified that this exemption was usually seen to refer to active military service.

Her reply to the Inn is treated as a renewed petition, which goes before Council in July 1921. She writes that she had been unable to take the Part I examinations in 1920 as she had not been allowed to tender her resignation at the end of 1919 to the Ministry of Food for the Midlands as planned, as ‘the ship was already sinking and it was not thought desirable to commission new officials.’ There is no recorded response but presumably the exemption could ultimately not be given.

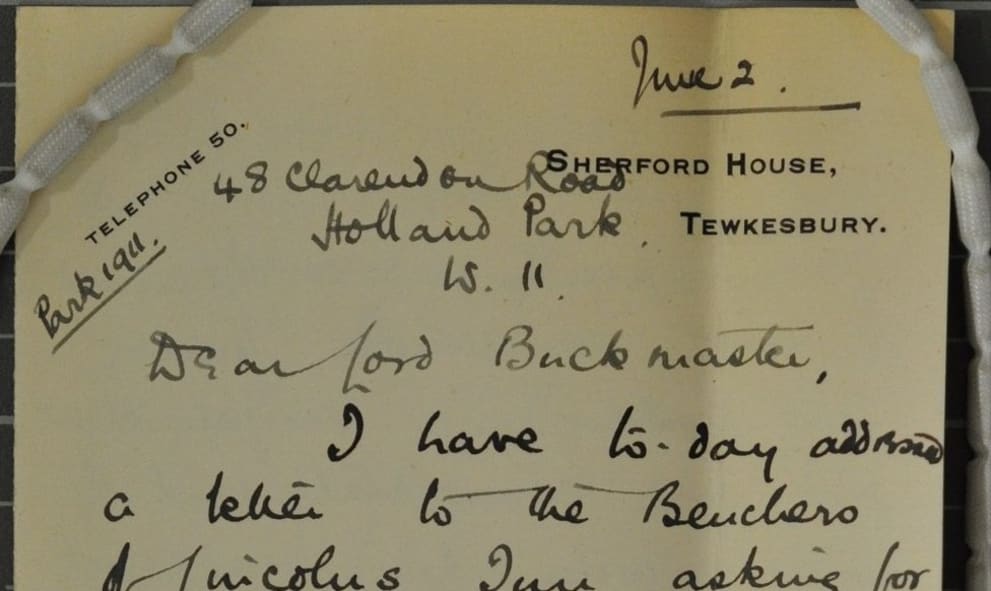

When submitting her petition to the Inn in June 1921 she also sends a letter to Lord Buckmaster, asking for his support if ‘you feel able to do so’. Her letter to him reveals the extent of her frustration and the sense of personal responsibility to represent the Inn to the fullness of her ability. She talks again of the demands of family and a job but also of her wish to ‘concentrate now as far as possible on my final or I fear I shall disgrace myself and my Inn.’ The passing of time since she completed her studies at Oxford, and undertaking the work involved in being called to the bar have proved difficult to reconcile. Her letter closes with a personal plea, insisting that any help he may be able to provide ‘would add years to my life!’

Gwyneth Bebb (as she was then) had finished reading Jurisprudence at St Hughes, Oxford in 1911, passing her law finals with first-class honours (making her the first woman at Oxford to do so). Her examination results were excellent and combined with her years of experience it would have been reasonable for her to have anticipated that she would be amongst the first women called to the bar.

After this second letter to the Council, the records go quiet. No subsequent call to the bar is recorded for Gwyneth. It transpires from other sources that, a couple of months after her petition to Council, Gwyneth gave birth to a second child on 10 August 1921. Sadly the baby was two months premature and died just two days later. Gwyneth was left fighting for her life, having suffered a post-partum haemorrhage and a cardiac arrest. She passed away two months later, at the age of 31.

Her story reveals much about the difficulties faced by women entering the legal profession even after the Act had been passed, as well as their struggle before. Her sustained fight for equality in the field that she worked and studied hard for, helped pave the way for others and makes her a notable figure in the history of women in law . For more information about the Women’s Forum being held at the Inn please see here. To learn about the First 100 Years Project, which is charting the journey of women in law since 1919, and is supported by the Law Society and the Bar Council, see their website.