January 2016 – Foundlings

The past practice of abandoning children in the hope they would be rescued and offered a better life elsewhere is well documented, with the instances of abandonment in London becoming so great during the eighteenth century that the Foundling Hospital was established in 1741 to provide care for many such forsaken children.

The Foundling Museum contains many interesting archives and very moving items relating to these foundling children. As it happens, the Inn has a direct connection to the Foundling Hospital in that Taylor White, Treasurer of the Inn in 1764, was Treasurer for the Hospital from 1746 to 1772.

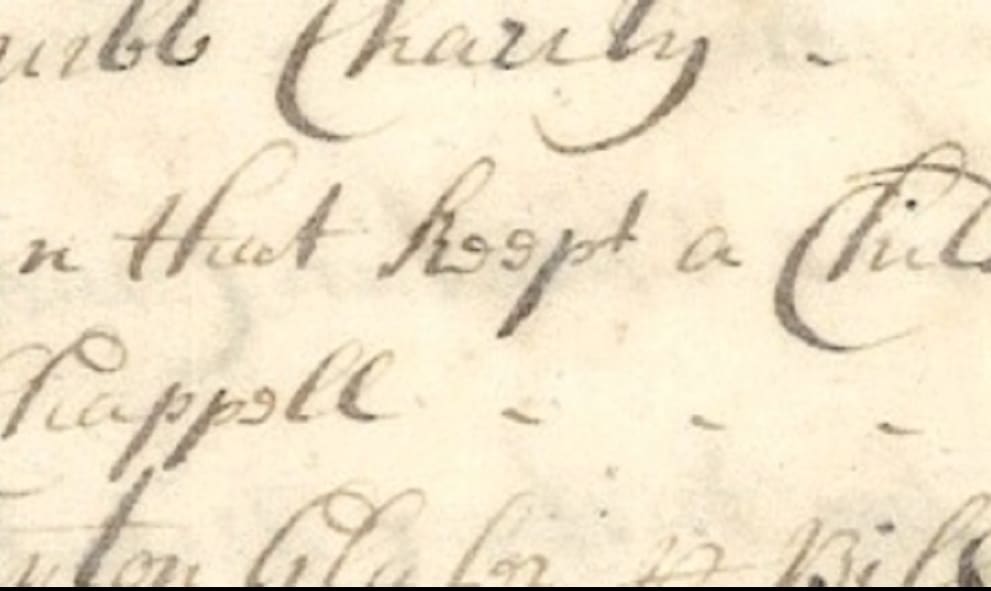

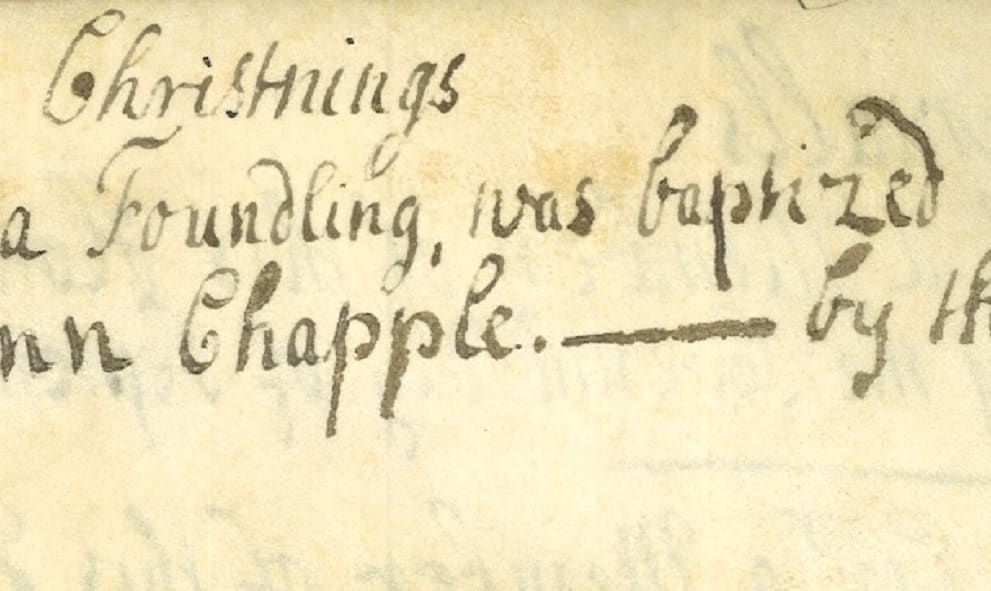

It is less well known, however, that the undercroft under Lincoln’s Inn Chapel was a favoured spot for children to be left. The first detailed reference, shown below, to a foundling at the Inn appears in the account books for 1732 where 2s 6d was given to ‘a woman that keept a child that was dropt under the Chappell’, although it is implied in the Black Books and accounts that babies had been left at the Inn before this date.

There are various subsequent references in the Inn’s accounts for payments being made to the Beadle of St. Andrew’s Holborn for ‘fetching’ children who were ‘dropt’ at Lincoln’s Inn, instances of this occurring in 1735, 1737, 1740, 1741, 1744, 1750, 1754.

There are also subsequent entries in the accounts for ‘nursing a foundling’ and ‘nursing children’ although some rather stark entries hint at the high infant mortality rates of the period. The accounts of 1732 list 12s 6d paid ‘for a coffin, shroud and all fees for the burial of one of them’ whilst another entry from 18 June 1777 shows that ‘the female child drop’d in this Inn be place out at nurse at the expense of this society’ with a note in the margin to say that this was done but that she died only a few months later on 18 October 1777. Lucy Lincoln (the surname ‘Lincoln’ was allocated to three of the foundling children discovered in the Inn) was found on the staircase of 22 Old Buildings on 18 June 1799 and was baptized in the Chapel on 7 July 1799 although sadly she died on 4 August 1800 the following year from small pox. She was buried in Bunhill Fields burial ground.

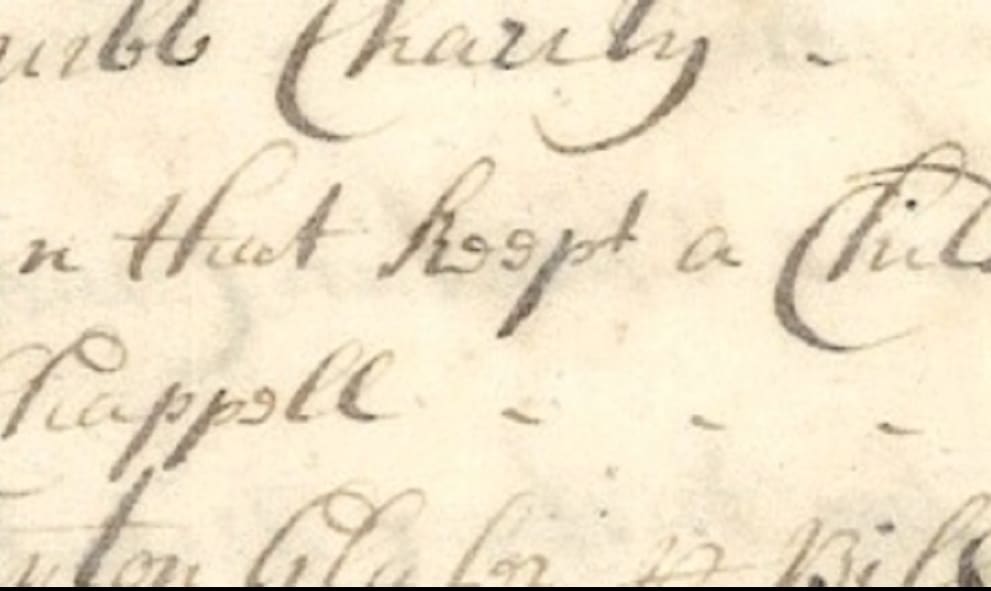

There were, however, happier futures for some of the Inn’s foundlings. Entries in the accounts for January 1777 list payments made to a William Britchfoot (a supernumerary porter who started working for the Inn in November 1773) for the care of George Lincoln.

Further research shows Thomas Grint, the Steward (a role equivalent to the present Under Treasurer) was initially responsible for the care of George including finding a nurse to care for him when he was discovered in 1774. George was baptised in the Chapel soon after his discovery and his entry in the baptism register can be seen below.

Further references in the accounts show the Inn paid 2s 3d for ‘a pair of stais, 1s 6d for a pair of shoes, 11s 9d for 3 frocks and making, and £4 18s for his board from September 12th 1774 to Feb 13th 1775’. Initially, George was cared for by a Mrs Britchfoot, who is likely to be the wife of William Britchfoot. The accounts for 1776 show further payments being made to William for George whilst additional money was allocated for the purchase of frocks, petticoats, shoes and aprons along with repair to existing frocks (possibly those ones mentioned in earlier accounts).

Later accounts for 1780 show £1 1s being given to Mary Bridgefoot (most probably the same person as Mrs Britchfoot) for ‘powders’ for George when he was bit by a ‘mad cat’. At a council meeting on 28 November 1782 it was decided George should be sent to Staindrop in County Durham to be taught at a school by a Mr Facer. The accounts for 1784 show a further payment to the Rev Mr Thomas Facer for the board and education of George. A lengthier entry in the Black Books from 4 June 1790 shows that at sixteen George was apprenticed for seven years to Thomas Langton, also of Staindrop. The last reference to George appears in the Accounts for 1791, with a note made to his annual allowance of £2 for his year’s ‘pocket money’. The move to County Durham certainly seems extraordinary, particularly when other Inn foundlings who were apprenticed moved no further than Middlesex. It would not be too difficult to imagine, however, that having effectively adopted and raised George before he was sent away, William and Mary Britchfoot may have hailed from County Durham and sent George there to live with, be taught by and be apprenticed to people they knew. Unfortunately it has not been possible to make this connection between the Britchfoots and County Durham using the usual parish and census records, although those same records suggest that our George Lincoln could be the same George Lincoln who married Ann Reed on 9 August 1803 and who died on 30 January 1831. He was buried at St. Mary’s Church in Barnard Castle, less than 6 miles from Staindrop where George originally went when he left the Inn. Unfortunately no memorial stone in St Mary’s graveyard survives for George Lincoln, the graveyard having undergone something of a reorganisation in the later 19th century, with some headstones being completely removed at this time.

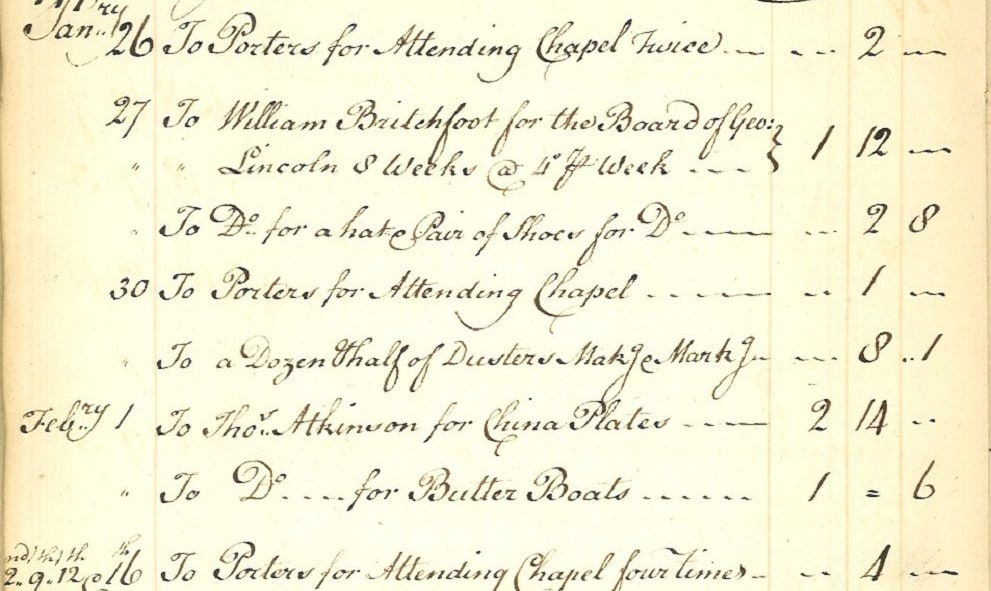

Although collectively this information is clear evidence that the Inn dealt with numerous foundling children throughout the eighteenth century, a 1774 report relating to the Inn contains an initially curious extract that suggests otherwise. It clearly states that no foundling children were ever found in the Inn. This statement was provided by the aforementioned Thomas Grint who, as has been seen, was directly responsible for finding a nurse for George. So why might Grint have suggested that the Inn had no dealings with foundlings?

To find out, please read the article about foundling children written by Mark Ockleton for the Inn’s Annual Review in 2011 (pp. 26-28), which can be downloaded from the right-hand side bar. The image below is a copy of the 1774 report.