January 2019 – The Spiritual Father of Pakistan

This month we feature a member who was according to Muhammad Ali Jinnah “a personal friend, philosopher and guide and as such the main source of my inspiration and spiritual support” as well as fellow barrister and political ally.

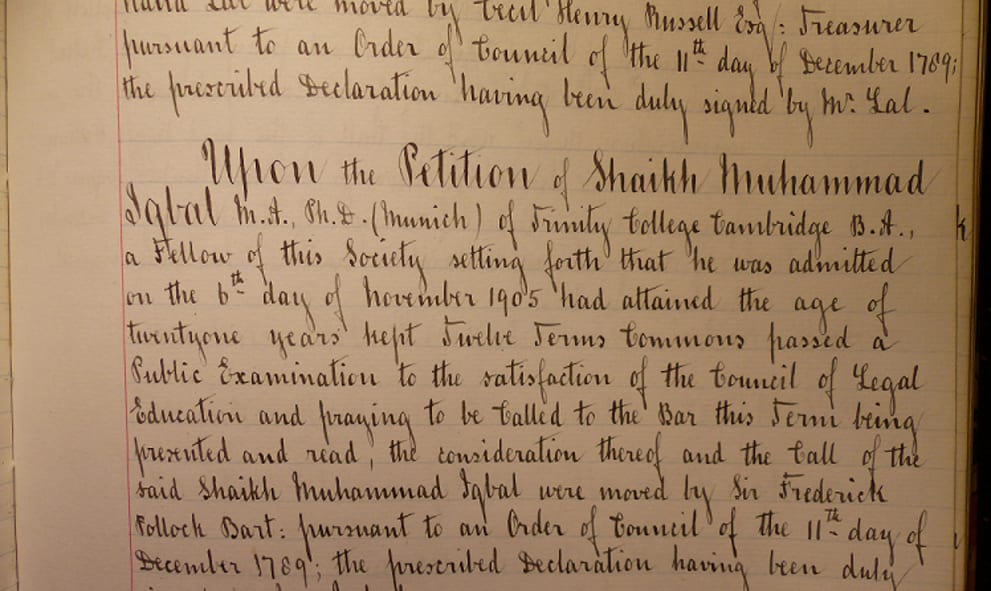

Although perhaps not so well known in the Inn as Jinnah, Sir Muhammad Iqbal played just as an important role in the formation of the state of Pakistan as his friend and colleague did. Iqbal was born on 9 November 1877 in Sialkot, in the Punjab province of British India (now Punjab, Pakistan). While attending the Government College Lahore he was influenced by the teachings of his philosophy teacher, Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, and was convinced to continue his higher education in Europe. Thus he came to Trinity College, Cambridge from where he was admitted to the Inn on 6 November 1905. He passed his bar finals with a class III pass in Easter term 1907, having graduated from Cambridge the previous year. He then went to Germany to pursue doctoral studies and graduated from Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich in 1908.

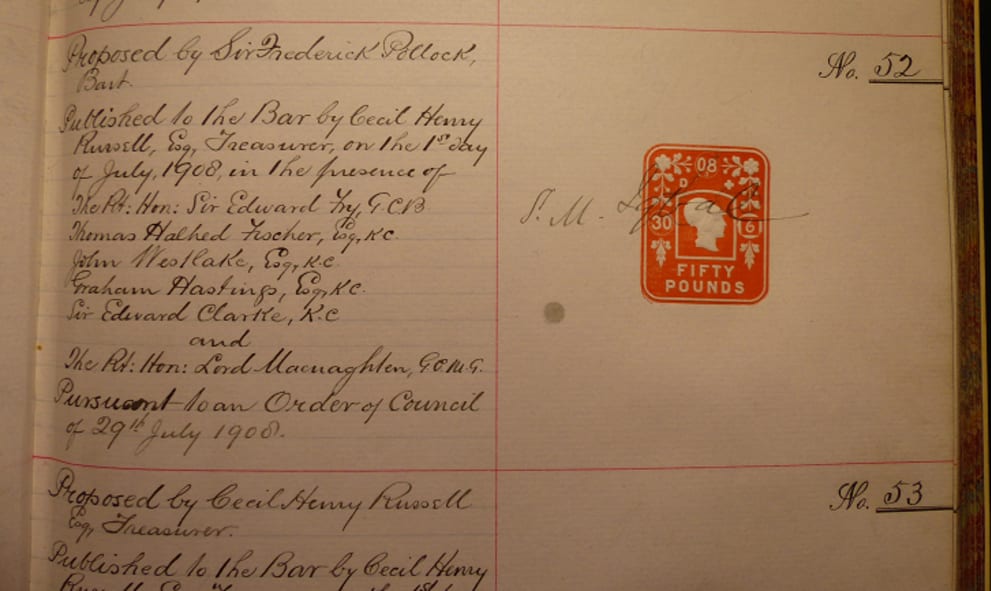

He was called to the bar here on 1 July 1908 having been proposed by Sir Frederick Pollock, the noted legal academic. It was the academic road that Iqbal then took returning to the Government College Lahore as a part-time professor of philosophy and English literature. This meant that he could also practice at the Lahore High Court. After a while he resigned his academic post to focus on law and poetry. He acted in both civil and criminal matters with more than a hundred reported judgements to his name and did not retire from practice until 1934. However it is not for law that he will be remembered but for his poetry, philosophy and politics. He had been interested in national affairs since his youth and became an active member of the Punjab Muslim League and was elected to a seat in the Punjab Legislative Assembly (1926-1930). In 1930 he was made president of the Muslim League and in his presidential address he famously out-lined his vision for an independent state “in northwestern India for Indian Muslims”. He believed that “the ultimate fate of a people does not depend so much on organisation as on the word and power of individual man”. He was one such man and saw this potential in Jinnah, whom he believed was the only political leader capable of preserving unity and fulfilling hopes for Islamic political empowerment. Sir Muhammad built up a strong personal correspondence with Jinnah who was then living here in England and was an influential force in convincing Jinnah to return to India. He said in one of his letters to Jinnah, “I know that you are a busy man but I do hope that you won’t mind my writing to you often, as you are the only Muslim in India today to whom the community has right to look up for safe guidance through the storm which is coming to North-West India and, perhaps, to the whole of India”. Indeed that storm was to come but Iqbal was not to see it as after a long illness he died in Lahore on 21 April 1938.

His dream that “nations are born in the hearts of poets” was realised in 1947 with the formation of Pakistan. He is held in such high esteem in that country that he is known as the nation’s poet and his birthday is a public holiday. His legal legacy has continued with two of his sons and a grandson all becoming Lincoln’s Inn barristers. One of his sons, Javed Iqbal (1924-2015), rose to be a justice of the Pakistan Supreme Court. His grandson, Aftab, following in his grandfather’s footsteps, is a poet and musician as well as legal counsel. Perhaps fittingly the last words on Sir Muhammad Iqbal should be those of Jinnah who after his death described him as “undoubtedly one of the greatest poets, philosophers and seers of humanity of all times. He took a prominent part in the politics of the country and in the intellectual and cultural reconstruction of the Islamic world. His contribution to the literature and thought of the world will live forever.”

Frances Bellis – Assistant Librarian