Chapter 2: The Case – Stewart vs Somerset (Black History Month)

James Somerset must have spent a very anxious eight months between his recapture and the final decision in the case. After the preliminary hearing in December 1771 the case returned to the King’s Bench in February 1772. It was heard by three judges with Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench presiding.

During this first hearing many of the arguments centred on comparisons between the status of slaves and that of ‘villeins’. Villeins were a class of people common in mediaeval England who were tenants bound to a particular individual or manor and subject to many restrictions, including the prohibition on leaving the land they worked without their lord’s permission. The main advocate for Somerset at this stage was Serjeant Davy, whose case, though well-armed with precedents and copious legal learning suffered somewhat from a number of digressions and a tendency to be vague in his references. Running out of time before the end of the Hillary (Spring) legal term, the case was postponed until May.

John Dunning and William Wallace, lawyers for Charles Stewart meanwhile produced precedents which supported the view that English law did recognise that a person might be owned as piece of property just as an animal or even a piece of furniture. Furthermore, they argued that if there was no clear English law forbidding slavery then there was nothing to prevent people owning slaves – even in England. They also stressed the economic consequences and likely social disruption of a decision which effectively liberated all slaves who were currently with their masters in England.

Ranged against Dunning and Wallace in this second hearing were Francis Hargrave and John Alleyne. The legal star of this second hearing was Hargrave. This was his first case and it made his name. (His portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds hangs in the Great Hall in Lincoln’s Inn)

His arguments (which he later published) dealt authoritatively and succinctly with Common Law precedent on the status of slavery in England and compared recent case law in other countries, such as France. He also considered the practice in the light of natural law, drawing heavily on Montequieu’s De l’esprit des lois.

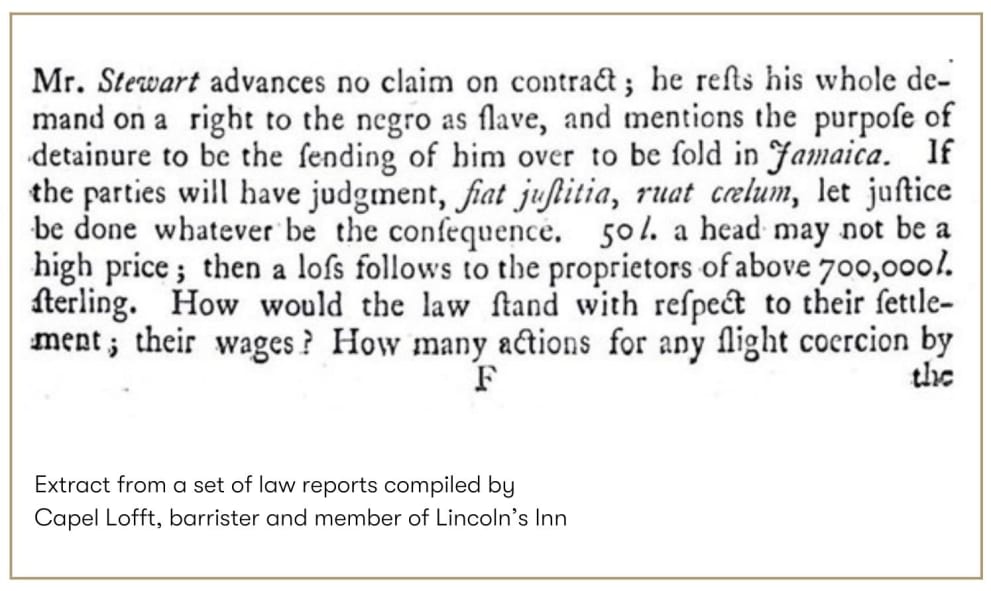

After the lawyers had finished their submissions, Mansfield was clearly unwilling to reach a judgment which would damage the country’s economy by limiting the slave trade and slavery in the plantations overseas. He attempted to evade this by persuading the parties to reach a settlement out of court. The parties insisted on a decision. On 21st May 1772, Mansfield recognised that the parties would not settle. He reserved judgment while he grappled with the conflicting demands of the case but, clearly, he anticipated making a judgment which would have major consequences. “If the parties will have judgment, fiat justitia, ruat coelum” [Let Justice be done, though the Heavens fall].

Next Friday: Chapter 3 – The Decision and Legacy of Stewart vs Somerset