Chapter 3: The Decision and Legacy of Stewart vs Somerset

On 22 June 1772 Lord Mansfield gave his judgment and James Somerset’s long wait for justice was over.

Mansfield ruled that as there was no previous legal decision which approved the practice of sending a person out of the country to a life of slavery and, as the practice of slavery is so abhorrent to any reasonable person, Stewart’s plan to send Somerset to the plantations as a slave could not be justified under the Common Law or by natural law. Somerset’s imprisonment was therefore illegal and he regained his freedom.

Somerset’s case had aroused a great deal of interest and Mansfield’s decision was widely celebrated and reported in the newspapers and in a set of law reports. Mansfield’s concluding words were particularly widely quoted – and misquoted:

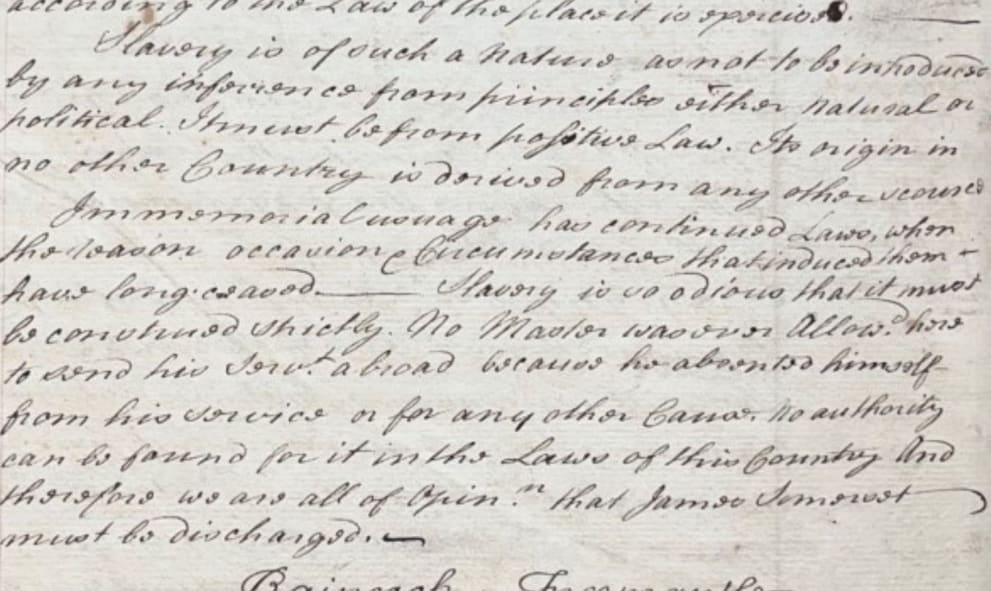

The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory : it is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.

Lord Mansfield's concluding words

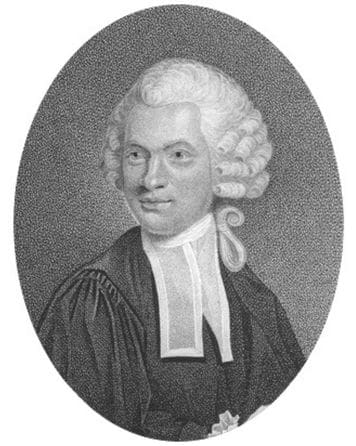

This version appeared in a set of law reports compiled by Capel Lofft (1751 – 1824), pictured below.

Lofft was a barrister member of Lincoln’s Inn and the author of a well-regarded series of law reports. His report of Somerset’s case was the most widely-circulated permanent copy. Other versions of the decision included newspaper accounts (very copies of which survived more than a few days) and a number of private manuscript copies.

These early copies are important for determining the accuracy of Lofft’s report. In addition to being a barrister, Lofft was also a committed anti-slavery campaigner. As with other anti-slavery campaigners, Lofft presented Mansfield’s decision as being more radical than intended. The quote above implies that slavery is so odious that, in the absence of an Act of Parliament (i.e. positive law) permitting it, no-one can be kept as a slave in England.

At this date, however, major cases were not transcribed and verified by the judge who gave the decision. Contemporary records of Mansfield’s words vary considerably. The Library includes a manuscript account of the decision by Serjeant Hill, a contemporary whose personal records of cases he witnessed are judged to be very reliable. Hill’s version of Mansfield’s opinion ends:

Slavery is so odious that it must be construed strictly. No master was ever allowed here to send his servant abroad because he absented himself from his service or for any other Cause. No authority can be found for it in the Laws of this Country. And therefore we are all of the Opinion that James Somerset must be discharged.

Serjeant Hill’s version of Mansfield’s opinion

In other words, in Hill’s version, the issue decided in the case was whether a slave could be detained in England and transported back to the plantations. Some years later, in R v Inhabitants of Thames Ditton (1785) Lord Mansfield expressly stated that [Somerset’s case] “got no further than that the master cannot by force compel him to go out of the kingdom”.

The niceties of the legal issues, however, evaded many contemporaries. Mansfield’s judgment was seen as deciding that a person could not be held as a slave in England and he became a hero of the abolitionist cause. Mansfield may have been reluctant to give a judgment which would damage the interests of British merchants and investors and his decision might have been far more limited than presented by the abolitionist movement. Nonetheless, all the accounts of the opinion include Mansfield’s view that the state of slavery is so odious that it could not be justified by natural law or reason.

The case did not, sadly, herald the end of slavery. It would take a further 35 years before the slave trade was abolished and slavery itself was not outlawed in the United Kingdom’s colonies until 1833. Mansfield had been unwilling to give any decision and the scope of his judgment in the case was more limited than campaigners presented it. Nonethless, the fact that Mansfield did not accept the arguments presented by Stewart’s lawyers in the interests of appeasing the country’s merchants was a milestone in the long road to abolition.

Next Friday: Chapter 4 – The Dido Belle connection